Version 12.1.0 |

Version 3.5.1 |

Version 2.2.1 |

Devised by the famous designer Nathanael Greene Herreshoff about 1903, the original Universal Rule of Measurement was created to solve a specific problem which had grown up in sailing. In solving this problem, it in effect created a whole new concept in sailboat racing, which is with us to this day.

At the turn of the last century, the most serious racing was done in a rule which rated only two of the three most major speed-related parameters of a sailboat: length and sail area. As either the length or the sail area increased, the rating increased. Little -- if anything -- else was considered.

What resulted was a boat which quickly became very extreme. To begin with, displacement wasn't rated at all, so it became less and less relative to the size of the boat, thus reducing the wave-making drag of the boat. At all but very low speeds, this drag accounts for about 75% of all of the drag of the boat in smooth water, so reducing displacement is very important. With no rule to regulate it at all, displacement became very light, and construction often became flimsy to keep the boat reasonably stiff despite the lack of weight.

Length was rated, but measured only at the waterline, so the old rule promptly produced boats with very long ends. Originated in various stages by the great designers George Watson, William Fife, and -- later -- Herreshoff, these long overhanging ends gave basically free length. This was itself no problem, but there was also no restriction placed on the fullness of these long ends, so that they quickly became very wide. When the shallow hull body that accompanied the light displacement was entered into the picture, the result was a very scow-like boat, very fast in moderate wind and smooth water, but not suitable for general racing, much less general use, at all.

These trends reached a limit in the 1901 America's Cup Challenger

Rigs on these boats were not regulated at all either, except by the measurement of the sail area they carried, so they naturally became large, light, and flimsy. Finally the 1903 America's Cup challenger

These experiences left many people, including Sir Thomas Lipton and Nathanael Herreshoff, with a determination that there had to be a better way.

So it was that Herreshoff wrote the Universal Rule of Measurement. This rule had a new, second purpose. Not only was the rule to provide an approximation of speed so that different shaped boats could race together with time allowance somewhat closely approximating their speed differences, but this rule was going to do something else: by means of its very rating formula and also a series of limits and penalties, it was going to force boats into a general, safer, saner shape and type.

The Universal Rule began with the concept of the older rule: rating goes up as sail area or length go up. But the new rule made rating go up as displacement went down also. That put a sharp limit on lightness in a boat, since there was a limit set below which weight was clearly discouraged from going.

Length was still measured at the waterline, but now a second length was added. This length was to undergo a great deal of alteration over the years, and pinning down its form at any point in history has now become a bit of a challenge. But the principle is that the length of the boat from a point on the topsides somewhere aft of the forward end of the waterline to a point somewhere aft of the aft end of the waterline will give an approximation of the wave length generated by the boat. Thus fuller ends -- which tend to make a longer wave form, especially as the boat heels over -- are taken into account by this length. Finally, a limit to this length relative to the waterline length was added, so that the full ends are not only rated, but also effectively limited.

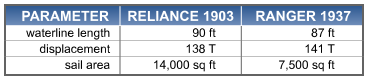

The boats which developed under the Universal Rule were as fully different from the earlier boats as anyone could possibly have intended. Comparing the last America's Cup defender built to the old rule,

This comparison doesn't tell the shape difference.

This comparison doesn't tell the shape difference.

A few years later, an international conference was held in Europe for a similar purpose -- to make a better rating rule. For reasons now lost in history, no Americans were present. This is sad, since a lot of common experience could have been used to make improvements to the Universal Rule. Instead a second rule was written, which accomplished the same purposes in some very different ways. This rule was the International Rule, which was put together in 1907.

The two rules produce surprisingly similar boats, up to a point. That is, they are both long, narrow deep boats, heavy by today's standards (though not by the standards of that day). These boats tend to be upwind standouts, but -- with the high displacement they are required to have -- are not remotely equal to the ultra light sleds of today going downwind.

Universal Rule boats are designated by a letter: A thru H were two-masted, I through S were single masted. The most famous were the larger sloop classes, especially Class J and Class M, and some of the smaller classes which were also very popular on the West coast, especially Class R.

The following table shows the ratings and maximum waterline lengths (under the 1926 length limit prescription by the New York Yacht Club, which was the rule-making body at that time).

It is vital to maintain the NYYC maximum waterline length prescription. This is one of the keys to maintaining the wonderful, classic appearance of the boats as Universal Rule boats, and also to maintaining a high life expectancy for the boats, as a major length change under these rules can spell the end of a boat's racing career.

It is vital to maintain the NYYC maximum waterline length prescription. This is one of the keys to maintaining the wonderful, classic appearance of the boats as Universal Rule boats, and also to maintaining a high life expectancy for the boats, as a major length change under these rules can spell the end of a boat's racing career.

The International Rule classes do not exactly correspond to the Universal Rule classes. In some cases they do nearly coincide: an S-boat is very close to a 6-Metre in waterline length, and a Q-boat very close to an 8-Metre. But in other cases, it seems like they more fall in between. The International Rule classes are well known even today, designated by their numbers which match their ratings in metres: the best known are the 12-Metre, 6-Metre, and 8-Metre. There was a full range of these boats too, going all the way from 5-Metre to 23-Metre.

From 1907 until 1931, the two rules both provided fine racing with the one problem that, if an owner of an International Rule boat wanted to race in the US or an owner of a Universal Rule boat wanted to race in Europe, he/she had to build a new boat. The two rating rules not only produced somewhat different boats, but the classes often didn't even correspond in terms of size. Even when they did, elements other than length might be different: Q-boats, for example, are only slightly longer than an 8-Metre, but tend to be much beamier, which has the advantage of there being considerably more room for an interior. Put simply, it was nearly impossible to race one rule's boats against the boats of the other rule without time allowance.

To solve this problem, the New York Yacht Club met in 1931 with representatives from Europe, and agreed that hence forth large boats would be built to the Universal Rule, and small boats to the International Rule. This decision made sense, since the Universal Rule seemed clearly -- by reason of its proportions -- to produce better large boats, and the International Rule became more popular for small boats.

To my mind, there is at very least one problem which has to be addressed right away, and that is the 1931 line between Universal and International Rule. For some reason drawn just above Class M, the line effectively ended building M boats, of which there were a number having excellent racing, in favor of a never-to-be-popular 14.5-Metre class. But I'd go further than simply correcting that...

Unlike the IOR era, when the idea was apparently that eveyone would race the same kind of boat to the same measurement rule, and thus be able to travel anywhere and fit right in with the local racing, in today's world people seem – understandably – to build the kind of boat they want, and take it to wherever the action in that kind of boat is. While that makes some problems that didn't exist the IOR way, to me it has a huge advantage: each owner can have the kind of boat that he/she wants, the kind of boat that he/she will really enjoy sailing. So while, at least, the dividing line between the Universal Rule and the International Rule needs to be lowered to a point between Class M on the Universal Rule side, and 12-Metre on the International Rule side, I think it is time to simply drop that agreement about the rules completely, and again have any size boat be built to whichever rule the owner wants.

The two rules produce somewhat different boats. The reason for this is mainly that the way the fullness of the ends is limited is so different. The International Rule uses girths near the ends to accomplish what the Universal Rule does by means of the second length measurement. Because of the way the that the girth length limits were chosen in the International Rule, that rule tends to produce a boat that is finer forward than aft, while the Universal Rule tends to produce a boat with more balance between the ends: perhaps slightly fuller forward, and somewhat finer aft, than a "metre boat", though we've reduced that different considerably in the New Universal Rule proposal. At the same time, it is much harder to fit the sail plan on the boat under the Universal Rule, so that the ends tend to be quite a bit longer, especially forward. The result is that, while the types are basically similar, an M boat is definitely not just a big 12-Metre. Many of the concepts developed for one will transfer to the other, but the designer must keep in mind the differences too, and a somewhat different boat results, though the basic proportions are similar.

Today there seems to be various kinds of revivals in both rules, but particularly in the Universal Rule. The J-Class of course draws a lot of attention, and the people behind it have unquestionably done a fine job in bringing that class back, with nearly a dozen boats either sailing, under construction, or in the planning stage. There is a group of people in the western USA and Canada now restoring or replicating the old R-Class boats and racing them, under an updated R-Class Rule, which like the present J-Class practice, doesn't allow new designs. In both those classes, the boats are either survivors from the old days, or replicas of boats from those days, or (in the J-Class), new builds of boats designed in the "old" days, but never built, of which there are actually quite a few to consider.

We are trying to do something a bit different. While the J-Class and the R-Class are basically recreating or restoring old boats and old designs, we have proposed a revised version of the Universal Rule to produce a modernized M-boat, but one which maintains the underlying character of the class: a long-ended, narrow, deep and powerful boat, but with many modern enhancements, and in which there is again design competition. That proposed new rule, and its supporting documents, can be downloaded from the links above.

We believe this revised rule will produce great racing and great sailing in a new version of a great and proven old class.

We hope you will review this proposed new rule, and -- whatever continent you live on -- agree with us that this successful, well-proven class, in it's proposed modernized form, is the right class for those who want a traditional type boat larger than a 12-Metre but smaller than a J-boat.